The knockoff culture - Part 1. Why do we copy?

Read in Indonesian

In this four-part series, TFR observed and analysed the roots of knockoff culture in Indonesia. The purpose of these articles is to educate, inform and provide solution to the issue.

Image: Vans filed copyright claims in April against Ventela for copying its design and iconic stripe. Instagram took down pictures of Ventela shoes on Ventela’s page and reseller accounts.

According to Calla The Label founder Yeri Afriani, "Designer referencing in Indonesia is common, it's hard to differentiate copycats with inspiration as it is all blurred…”

She experienced plagiarism firsthand when she discovered that two factories in Jakarta worked with another brand to mass-produce her designs. This is a common occurrence all over the world, even among luxury manufacturers.

Maryallé has also dealt with this issue: "Unfortunately yes, Maryallé has caught many customers that bought our creation and copied our design with the same exact pattern. Even worse, they sell them at a much lower price. It is very heartbreaking to see how people just easily copy my effort and creativity for their own personal gain."

One of the encouraging factors to this notorious copying culture is the regulatory loopholes. Generally, the copyright law only covers graphics, sculptures, images, music choreography, computer programs and codes, literature, architecture and games, but excludes works related to the development of clothing brands.

Clothing, bags and shoes are not protected by the copyright law since they are considered 'functional' items, and they were invented to solve technical problems. Clothes prevent humans from going out nude, while shoes prevent them from going barefoot. Together with bags and other accessories, they add to the comfort of humankind. That means the pattern of a garment can be duplicated without giving rise to legal battles.

Unfortunately, this is a universal law. France is the only country to tighten copyright law for clothes since fashion is the country's main commodity.

Back in 2018, British-Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor filed a lawsuit against Kendrick Lamar and SZA for using her artwork in their "All the Stars" music video for the movie Black Panther without her permission. She said the film creators contacted her twice asking for her permission to feature her work in the video, but she declined both times.

The letter sent to the creators of the music video detailed a 19-second segment “that incorporates not just the immediately-identifiable and unique look of her work but also many of the specific copyrightable elements in the 'Constellations' series of paintings, including stylised motifs or mythical animals…"

A copyright lawyer, Nancy E. Wolff, who currently serves as the president of the Copyright Society of the USA, explained that the video creators are likely to argue that they are not exact copies. However, due to Viktor's strong gold-on-black colours, Wolff said, "It's just going to look like it's the same."

Again, in the same way as it is in fashion--the style is not protected.

"I still buy fast fashion because they are accessible. I only buy high-end pieces like blazer, shoes and bags that will last for a long time,” said a 28-year-old respondent.

A 16-year-old respondent said, “I resort to fast fashion when I cannot find the right fit at thrift stores. It’s difficult to find pieces that are in good condition or suitable for more formal settings at thrift stores.”

It’s not only in the fashion industry. Knocking off or adopting has been ingrained in other sectors like business and culture. According to sociologist Everett Rogers, there are five adopter categories - innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards.

Image: Five adopter categories/TFR

Innovators are people who want to be the first to try the products. They are willing to take risks and explore even though the products might fail. Only 2.5% people in the market are innovators.

Early adopters are known as visionaries. They are almost similar to innovators--willing to take risks and invest in a new product. However, early adopters are more concerned about maintaining their reputation as being ahead of the curve.

On the other hand, people in the early majority category are willing adopt when the products have gained momentum or they have proven to be successful.

Late majority is similar to early majority, but they will only commit to a product if they receive help and support.

Laggards will use a product only if they have to. They tend to stay in their comfort zone. Around 16% of people in the market falls under this category.

Based on the characteristics above, Indonesia falls under the late majority category. An investor at the 2019 Ideafest said, “Indonesia is 10 years behind in technology. It’s been done overseas for 10 years before it enters Indonesia.”

This can be seen in the recent bloom of tech start-ups in the country. E-commerce is growing rapidly in Indonesia, while Amazon has started operations since 1994. If we compare the big picture, brands and companies in the US and Europe have been pushing sustainability efforts and inclusivity into their brand value.

The manufacturing sector has also been experimenting with robotics and automated sewing bots. US-based SoftWear Automation, for instance, disrupted the clothing manufacturing process with robotics and advanced computing.

Meanwhile, Indonesia is still grappling with data and security breach, as seen on recent data breach on Tokopedia, one of the leading e-commerce companies in the country. Adding to the injury, interface and user experience are overlooked on many websites.

In the manufacturing sector, companies are eyeing Indonesia for cheap labour. Some companies like Shanghai-based Tuntex set up production facilities whilst bringing the tech into the country. In fact, the Chinese government is pushing the country’s manufacturing sector to become the global leader through the Made in China 2025 initiative that aims to deploy high-tech manufacturing technology.

Image: Food vendor in Surabaya, Indonesia via Unsplash

Another factor is entrepreneur’s mindset. Although around 35% of Indonesian youths is entrepreneurs, it’s worth noting that a lot of Indonesians create a business to escape minimum wage jobs. Some create businesses due to poor access to education. Take, for example, stalls and street food sellers. It is their only option to survive. Hence, profitability over innovation.

Moreover, in order to innovate, companies have to conduct product research, experiment and development. They need human resources, effort, cost and time - not all businesses can afford them. SoftWear Automation, for instance, took seven years of research.

As a result, many business owners prefer creating and running a proven business model to taking big risks on innovation. Reliance on import is one of the evidence. According to Statistics Indonesia (BPS), imports of consumer goods increased 7.11% from January to March 2020. Selling imported product that is already popular overseas and has been certified is the safest option.

This is also prevalent in brands that recreate trending products. How many make-up brands launch lipsticks after Kylie Jenner launched her lip kits in 2018?

The hype from the products they adopt proves that the products are well-received in the market, thus eliminating the risk of failing. This is also one of the late majority traits.

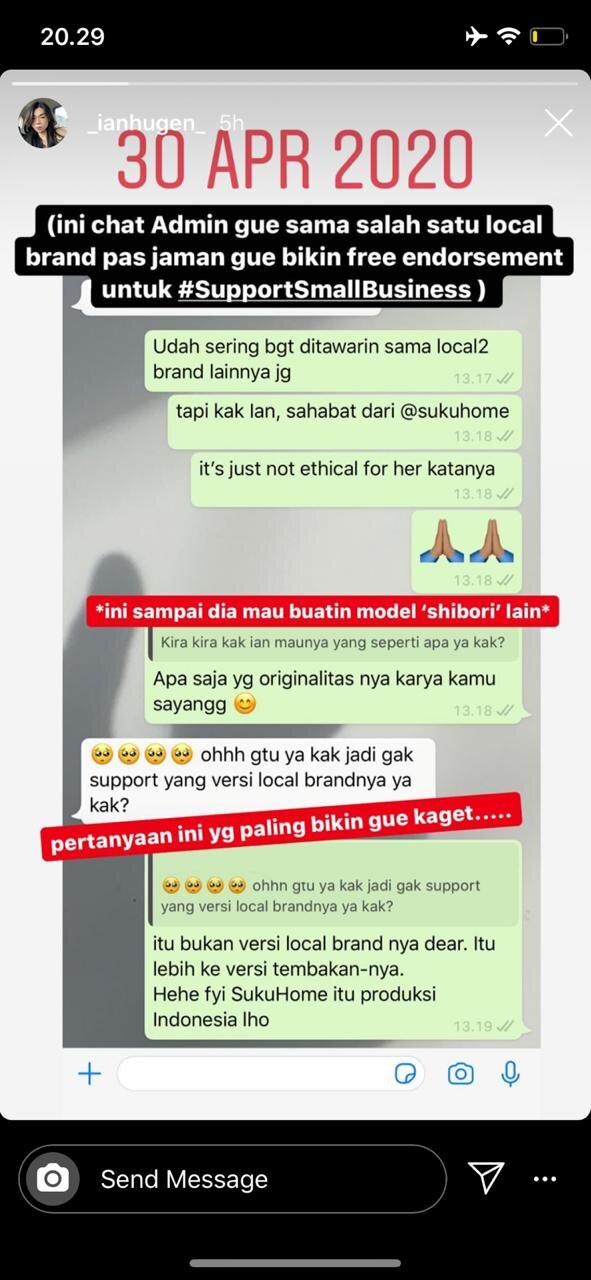

Image: Ian Hugen’s Instagram story sent to TFR as reference

Ian Hugen, a social media influencer, has been advocating creative thinking in the Indonesian creative industry. On her recent Instagram post, she said that she often received requests from brands that replicate concept and designs of well-known brands and introduce them as the local version.

“A lot of them don’t know the difference between inspiration and straight up copying,” said Ian. “One of the brands I turned down even schooled me back saying ‘this brand doesn’t own shibori,’ but that’s not the point.”

Plagiarism, imitation, copycat and knockoff hold the same meaning - the act of using other’s work and passing it as their own regardless of small changes or modification. The use of those words depends on the context.

Plagiarism often refers to literature, imitation to describe jewelry, copycat to describe designs and knockoff to describe fashion. They are often mixed up with counterfeit. Counterfeiting is an act of replicating design and trademark. The keyword here is trademark. Counterfeit is against the law. Take, for example, luxury bag counterfeits.

Plagiarism, imitation, copycat and knockoff don’t use logo and trademark of other brands on their products. They simply copy the idea, concept and designs then modify or alter the elements like material, colour and graphic.

For instance, the case of Ventela and Vans. Although one may argue that the stripe on the side of Ventela shoes is not similar to Vans, switching the stripe upside down is still considered as knockoff because it is the concept of the shoes that is similar.

The build of the shoes, the use of stripes and, most importantly, the overall look of the shoes are associated with Vans.

It’s the same with the shibori case. Like ikat, shibori doesn’t belong to anyone because it is a technique. It is the concept and design that make products look similar to one another.

That brings us to the last point, favouritism toward Western culture. Whether we realise it or not, favouritism toward Western culture plays a role in grooming an adopter culture among Indonesians or, in other words, colonialism culture.

Back then, the Dutch colonial government implemented a racial segregation policy within the Indonesian society. The Dutch held the highest power, followed by the Arabs and Chinese. Native Indonesians were categorised as inlander, a derogatory term given by the Dutch colony.

As National Geographic puts it, “The concept of colonialism is closely linked to that of imperialism, which is the policy or ethos of using power and influence to control another nation or people that underlies colonialism.”

The remnants of colonialism remain visible up to this day. Assuming white as a superior race is one of them. In return, it leads to the loss of cultural identity as a lot of people are subconsciously complying with the Western standards. To prove this statement, look no further to the society’s perception of beauty. Light skin is hailed as the beauty standard.

Transitioning from an adopter culture to innovative is a long-term commitment. Support from consumers, the government and investors will help push the agenda forward. Creators or entrepreneurs need to firmly establish a critical thinking and problem solving mindset. Indonesia’s creative industry needs to support this notion continuously.

The focus should be on pushing quality and individuality. Indonesian brands should not always conform to the trends, but transgress and blur the societal norms.